This is the fifteenth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to participate in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Bee, which will be held on September 23.

The Eighth Amendment contains one of the most famous phrases in American judicial history: “cruel and unusual punishment.”

That phrase over the past half century has been the rallying cry around which opponents of capital punishment gather.

But the Eighth Amendment is an important protector of two other rights: the prohibition of excessive bail requirements and the prohibition of the imposition of excessive fines:

Excessive bail shall not be required, not excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

The amendment protects the rights of the individual by prohibiting three specific acts of the state:

(1) Excessive bail shall not be required.

(2) Excessive fines shall not be imposed.

(3) Cruel and unusual punishment shall not be inflicted.

We begin our discussion of the Eighth Amendment with the best known clause: the prohibition of “cruel and unusual punishment,” which opponents of capital punishment have cited over the past half century as proof that the execution of prisoners for murder or any severe crime is not constitutional.

There are two elements here to consider.

First, the standard that applies is what the Framers considered to be “cruel and unusual punishment” at the time the amendment was ratified in 1791. The world two hundred years ago was much different than the world we live in today.

Some things people consider to be “cruel” today were, in many cases not given a second thought in 1791, nor were they considered out of the ordinary.

“Unusual punishment” in 1791-even in the United States and England–has a different connotation than it does in modern America.

CRUEL AND UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT AND THE DEATH PENALTY (Capital Punishment)

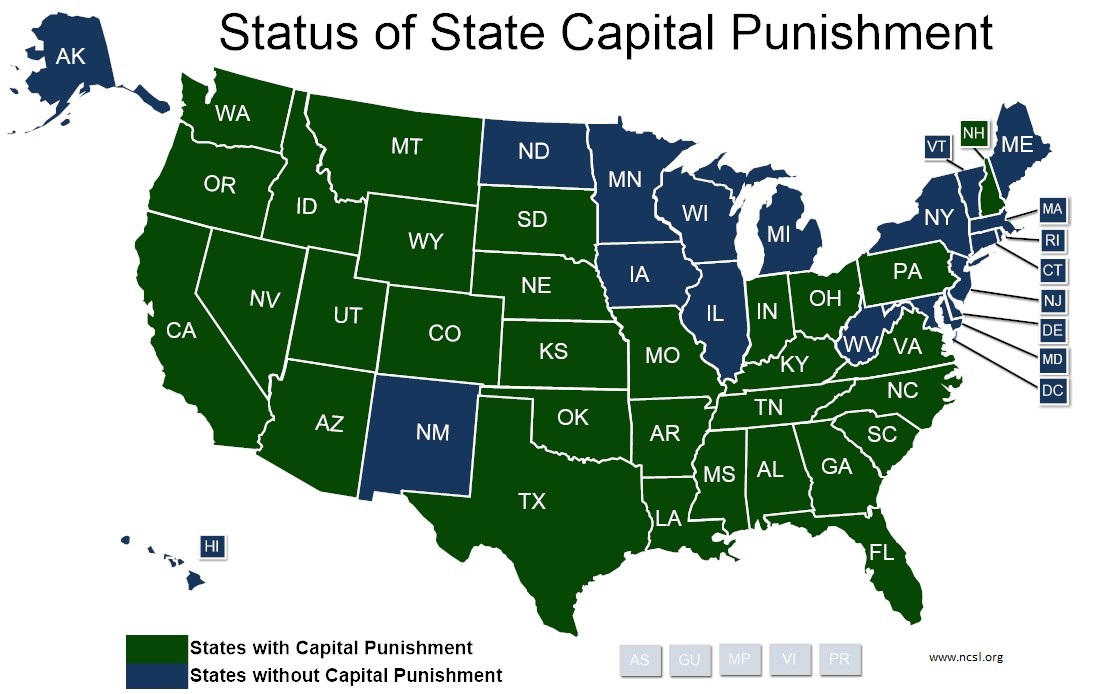

“Capital punishment is currently authorized in 31 states, by the federal government and the U.S. military,” according to the National Conference of State Legislatures:

In recent years, New Mexico (2009), Illinois (2011), Connecticut (2012) and Maryland (2013) have legislatively abolished the death penalty, replacing it with a sentence of life imprisonment with no possibility for parole. The Nebraska Legislature also abolished capital punishment in 2015, but it was reinstated by a statewide vote in 2016. Additionally, courts in Delaware recently ruled that the state’s capital punishment law is unconstitutional. States across the country will continue to debate its fairness, reliability and cost of implementation.

Since colonial days, capital punishment had been considered a legal and appropriate punishment for the crime of murder, and other similarly heinous offenses.

In the 1950s, political opposition and legal challenges to the death penalty began to increase. The number of executions for capital crimes began to decline.

In a 1972 case, Furman v. Georgia, the Supreme Court ruled in a 5 to 4 decision “that the imposition and carrying out of the death penalty in these cases constitute cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. The judgment in each case is therefore reversed insofar as it leaves undisturbed the death sentence imposed, and the cases are remanded for further proceedings.”

Four years later in 1976, the Supreme Court held in a 7 to 2 decision in the case of Gregg v. Georgia that capital punishment was constitutional:

The basic concern of Furman centered on those defendants who were being condemned to death capriciously and arbitrarily. Under the procedures before the Court in that case, sentencing authorities were not directed to give attention to the nature or circumstances of the crime committed or to the character or record of the defendant. Left unguided, juries imposed the death sentence in a way that could only be called freakish. The new Georgia sentencing procedures, by contrast, focus the jury’s attention on the particularized nature of the crime and the particularized characteristics of the individual defendant. While the jury is permitted to consider any aggravating or mitigating circumstances, it must find and identify at least one statutory aggravating factor before it may impose a penalty of death. In this way, the jury’s discretion is channeled. No longer [p207] can a jury wantonly and freakishly impose the death sentence; it is always circumscribed by the legislative guidelines. In addition, the review function of the Supreme Court of Georgia affords additional assurance that the concerns that prompted our decision in Furman are not present to any significant degree in the Georgia procedure applied here.

For the reasons expressed in this opinion, we hold that the statutory system under which Gregg was sentenced to death does not violate the Constitution.

The political and legal arguments for and against capital punishment continue.

“There are two reasons for arguing that the death penalty is a “cruel and unusual punishment”, and thus unconstitutional,” The Economist Magazine, a long-established British publication that covers American political and legal issues, argued in 2014:

One was on grim display in Arizona on July 23rd, when Joseph Wood, a double-murderer, took nearly two gasping, choking hours to die by lethal injection. The other came under legal attack on July 16th, when a federal judge, Cormac Carney, struck down capital punishment in California for being too slow and capricious.

Of the more than 900 people California has sentenced to death since 1978, only 13 have been executed. The last one died in 2006. The same year, a federal court ruled that California’s mode of lethal injection carried a risk that “an inmate will suffer pain so extreme” that it should be considered cruel and unusual.

With Mr Carney’s ruling, the state’s system of capital punishment has been judged doubly unfit. The average prisoner who is executed in California has spent 25 years on death row—much longer than the national average of nearly 16 years. Such long delays make it unlikely that capital punishment deters other potential murderers, ruled Mr Carney.

Nonsense, say supporters of maintaining capital punishment for those who commit heinous crimes.

“No serious constitutional argument can be made against the death penalty. The endless campaigns to ban it cost taxpayers millions to defend,” attorneys David Rivkin Jr. and Andrew Grossman wrote in an op-ed at the Los Angeles Times in 2011:

Every legal argument against the death penalty begins with the 8th or 5th Amendment. The 8th bars “cruel and unusual punishments,” and the 5th guarantees “due process of law” before a person can be “deprived of life, liberty or property.” But there is no serious constitutional argument against the death penalty. The 5th Amendment itself recognizes the existence of “capital” crimes, and executions were common before and after the Constitution’s framing. No framer ever suggested that the Constitution divested states of this part of their historical punishment power, nor has there been a constitutional amendment that does so.

Matters not addressed by the Constitution are left to the democratic process and, in the main, to the states. As in Europe and Canada, a solid majority of American citizens supports the death penalty, believing it to serve both as a deterrent and an appropriate societal response to particularly heinous crimes. Unlike in Europe and Canada, however, U.S. courts and political leaders have not overridden public opinion to end the practice.

But they have tried. At the tail end of the criminal rights revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, the Supreme Court put a halt to all executions. While the public acquiesced or supported other innovations in criminal law, such as Miranda warnings, the death penalty moratorium was less well received. Pushed by their citizens, states passed new laws requiring juries to find specific “aggravating factors” justifying the death penalty, and in 1976, the court allowed executions to resume on that basis.

A Gallup Poll conducted in 2004 found “that three-fourths (75%) of Americans agree that ‘states should be allowed to execute prisoners sentenced to the death penalty by means of lethal injection.’ Twenty-one percent said it should not be permitted because it is a form of cruel and unusual punishment.”

OTHER APPLICATIONS OF CRUEL AND UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT

The “cruel and unusual punishment” clause has been applied to punishments other than capital punishment as well. One such punishment is loss of citizenship.

“Divestiture of the citizenship of a natural born citizen was held in Trop v. Dulles, again by a divided Court, to be constitutionally forbidden as a penalty more cruel and “more primitive than torture,” inasmuch as it entailed statelessness or “the total destruction of the individual’s status in organized society,” the Legal Information Institute noted:

EXCESSIVE BAIL

Chief Justice Fred Vinson’s majority opinion in the 1951 case Stack v. Boyle expressed the Court’s view on excessive bail.

“This traditional right to freedom before conviction permits the unhampered preparation of a defense, and serves to prevent the infliction of punishment prior to conviction. . . . Unless this right to bail before trial is preserved, the presumption of innocence, secured only after centuries of struggle, would lose its meaning,” Vinson wrote.

“The bail clause was lifted with slight changes from the English Bill of Rights Act. In England that clause has never been thought to accord a right to bail in all cases, but merely to provide that bail shall not be excessive in those cases where it is proper to grant bail. When this clause was carried over into our Bill of Rights, nothing was said that indicated any different concept,” Justice Stanley Reed wrote a year later, in the Court’s majority opinion in Carlson v. Landon.

EXCESSIVE FINES

The excessive fines clause of the Eighth Amendment was largely a footnote for some time, but that has changed in the past several decades.

“The “excessive fines” clause surfaces (among other places) in cases of civil and criminal forfeiture, for example when property is seized during a drug raid,” the Legal Information Institute reports.

“For years the Supreme Court had little to say with reference to excessive fines,” the Legal Information Institute reported:

In an early case, it held that it had no appellate jurisdiction to revise the sentence of an inferior court, even though the excessiveness of the fines was apparent on the face of the record. In a dissent, Justice Brandeis once contended that the denial of second–class mailing privileges to a newspaper on the basis of its past conduct imposed additional mailing cost, a fine in effect, which, since the costs grew indefinitely each day, was an unusual punishment proscribed by this Amendment. The Court has elected to deal with the issue of fines levied upon indigents, resulting in imprisonment upon inability to pay, in terms of the equal protection clause, thus obviating any necessity to develop the meaning of “excessive fines” as applied to the person sentenced. So too, the Court has held the Clause inapplicable to civil jury awards of punitive damages in cases between private parties, “when the government neither has prosecuted the action nor has any right to receive a share of the damages awarded.”

As political controversies over the death penalty and civil asset forfeitures continue to expand, the Eighth Amendment is likely to be an increasingly relevant part of the Constitution in future Supreme Court decisions.